Education and Training of Researchers

Education and Training of Researchers

Identifying and leveraging existing learning resources for ACI topics and resources. Developing novel materials for in-person learning and self-directed learning, including both education (knowledge/awareness) and training (skills/practice). Leveraging established practices for effective teaching.

- Introduction

- Overall Considerations

2.1 Identify Gaps

2.2 Pursue Multiple Learning Formats

2.3 Leverage Existing Materials

2.4 Organize and Promote Learning Materials for Ease of Use

2.5 Obtain and Integrate Feedback

2.6 Infrastructure Needed for Material Development - Content Development Strategies

3.1 Establish goals of the learning material

3.2 Clearly communicate prerequisites and limitations

3.3 Organize content within conceptual units

3.4 Clarity and Brevity

3.5 Use Visual Aids

3.6 Assess and revise, continually - Format-Specific Considerations

4.1 Written Materials

4.2 Verbal Formats - Promoting Learning between Researchers

- References

Introduction

As an essential component of supporting any cyberinfrastructure resource, documentation and training materials add to the range of formats by which researchers can learn to most effectively leverage ACI resources. Such materials not only serve as an important complement to engagement and assistance activities, but are often - and should be - informed by these activities. Facilitators are generally poised to be most familiar with user interfaces to ACI resources and with the range of researcher experiences and feedback; therefore, Facilitators should be able to organize, produce, and deliver functional learning resources for ACI users.

For the purposes of defining the activities of Facilitators in this space, education will refer more to materials and efforts to promote knowledge and understanding of ACI resources, while training will describe guided opportunities for researchers to develop specific skills needed when applying ACI resources to their work. Importantly, though, these two terms are not mutually exclusive, and many learning opportunities will include a combination of education and training.

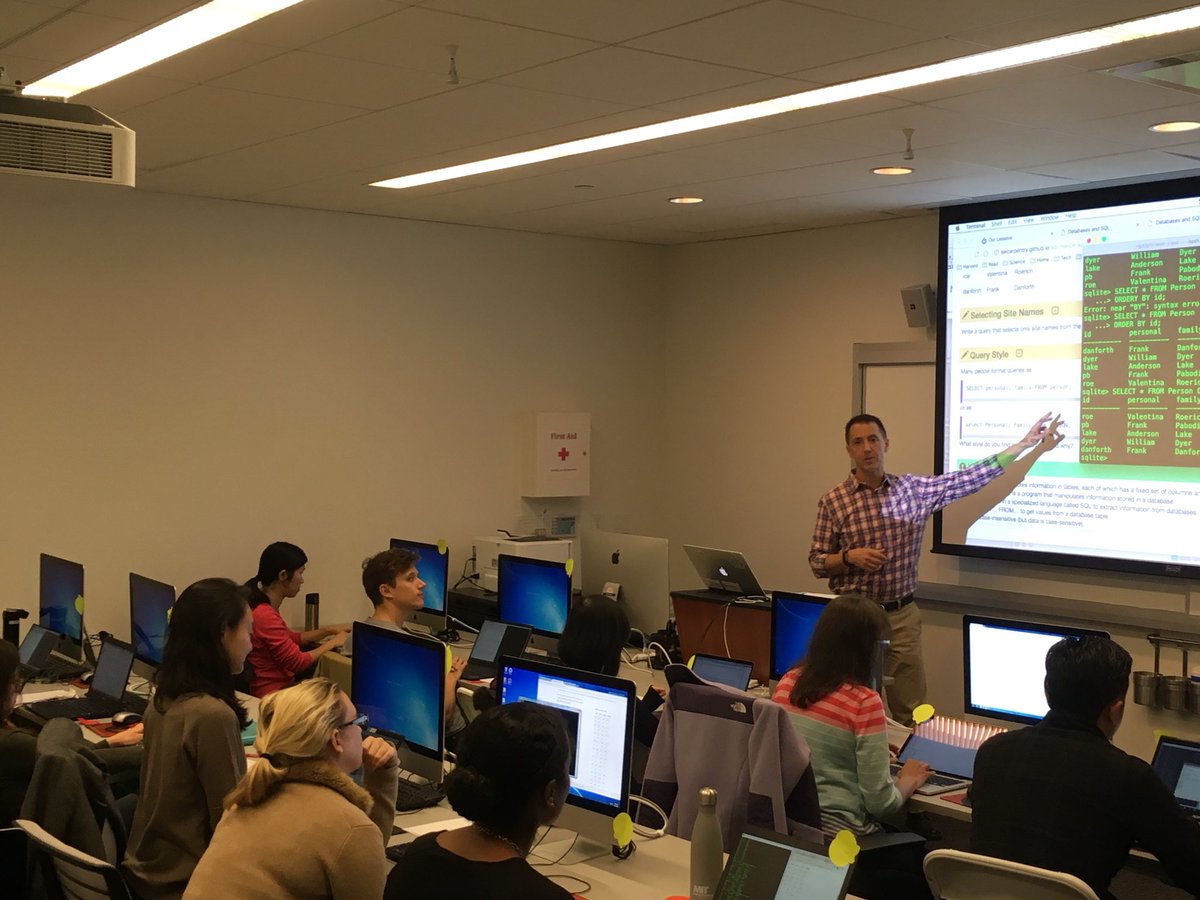

Researchers attend an research computing workshop.

Researchers attend an research computing workshop.

Furthermore, there are certainly overlaps between this chapter and that for Outreach, as some information delivered in outreach efforts might certainly be thought of as educational. However, we distinguish outreach and education, for the purposes of defining leading practices, by their intent: whereas, outreach was previously described as efforts to promote awareness of ACI services and resources (including the Facilitator role), as well as their general usefulness to research, education will refer to information on how ACI resources work and how to use these resources to specific research needs. For example, a presentation promoting the various services of a campus research computing center, delivered to a mixed audience of mostly non-users (or not-yet-users), can be thought of as outreach. However, a presentation giving new or intended users of a compute cluster details of job scheduling, partitions/allocations, and submission files will be described as education within this chapter.

We thus provide the following examples of education and training efforts for users of ACI resources, which can and should be significantly contributed to by Facilitators:

- online documentation of ACI system configuration (e.g. cluster partitions, etc.)

- online FAQs for using ACI resources

- step-by-step instructions for accomplishing specific tasks on ACI resources

- one-to-many training for various skills in using an ACI resource

- videos explaining aspects of using ACI resources

Many of these different types of learning materials and opportunities are described later in this chapter, drawing on the “Overall Considerations” just below. We additionally cover general considerations for composing and delivering training materials and for incorporating external materials into an overall structure for supporting the learning needs of users of an ACI resource.

It is important to state that many of the ideas behind the tips and practices in this chapter are not original. There exists a plethora of established research and leading practices guidance for the production and delivery of education and training materials, including and reaching beyond materials specific to cyberinfrastructure. We reference several resources with informative conclusions from such research. However, the information presented in this chapter should be thought of as more of a gateway into other ideas, as we cannot be exhaustive. Not all Facilitators will spend significant time preparing and presenting materials for researcher learning. Those who do will benefit from consulting additional resources on education and cyberinfrastructure training, and on technical writing. Furthermore, a plethora of examples of education and training examples exist for similar ACI resource providers, including national resources.

Jump to: top

Overall Considerations

Regardless of the format of learning materials or their delivery (verbal versus online text), there are overall practices and strategies that will enable Facilitators and other ACI staff to develop these materials for maximum effectiveness and production efficiency. In the following text, we list and describe many of these considerations, though many of them are also later discussed in the topics of “Composition Strategies”, “Delivery and Teaching”, “Written Formats”, and “Verbal Formats”.

Identify Gaps

In order to inform education and training efforts, Facilitators should regularly reflect on interactions with researchers to identify the most common and important gaps in user understanding and gaps in existing learning materials. Informative interactions will not only include engagements and assistance with issues (including assistance tickets of other staff), but also researcher reflections in pro-active support and information obtained through assessment of user satisfaction with existing learning materials (see Assessment and Metrics). Some learning gaps may require simple updates to existing materials, while others require the creation of new materials. Another form of a gap in learning materials might be the lack of multiple formats, in which case the material might be made preferable for more researchers by pursuing an additional format. In some instances, especially for information that is generally relevant in a wide range of contexts (beyond the context of any one specific ACI resource), Facilitators can simply point researchers to existing, external documentation (see “Leverage Existing Materials”, below). For additions of in-house materials, we later describe the importance of defining learning modules to specifically satisfy pre-defined learning outcomes to fill known gaps (see also 1).

Often, a nearly unending number of topics could be newly documented or taught, so it is important to also consider which topics have the greatest need for new learning materials, based on how essential each topic is to the overall use of the ACI resource and on how often researchers tend to struggle with them. Knowledge gaps applicable to individual researchers may be best addressed in one-on-one assistance explanations, whereas information consistently misunderstood by multiple researchers will typically justify the addition of a specific online tutorial or FAQ entry.

Pursue Multiple Learning Formats

It is often the case that different people will prefer certain formats over others, and that this preference may depend on the material being taught. A combination of formats may be applied within the same learning material (e.g., a general explanation followed by step-by-step instructions, a step-by-step guide that includes an FAQ component, etc.). Furthermore, materials for training researchers in skills and practices may be best delivered for some researchers as guided, workable examples rather than hypotheticals, and others may still prefer one-to-one assistance for directly applying specific practices to their specific use-case(s), rather than examples. (See 2 for more on guided instruction.) As a result, we suggest that Facilitators develop and promote multiple learning formats, (see “Written Formats” and “Verbal Formats”) and include avenues for obtaining one-to-one assistance described previously in Assisting Researchers in the Use of ACI Resources. Similar to the reason for providing assistance via multiple communication pathways to accommodate researcher schedules, in-person learning materials should also be available for independent learning by researchers who can’t attend a pre-scheduled event.

Leverage Existing Materials

Often, topics that researchers need to learn about will not require the creation of new materials as existing materials may be sufficient. For example, highly-generalizable skills that apply to similar ACI resources are often covered well in a number of other resources, especially online materials (e.g., guides for the unix shell, text editors, or common command-line file transfer tools). For in-house materials, it is often important to point to such external references when introducing a specific skill within a greater step-by-step example. However, there are certainly instances when generalizable information will be most effective when actually embedded within Facilitator-created materials instead of simply pointing to external sources and drawing the user’s attention away from the overall workflow. For example, specific illustrative ‘tar’ commands might be included in a guide for transferring large files between specific remote systems, rather than simply stating that files should be tar’d and pointing to a different guide about the ‘tar’ program.

Some examples of external learning materials are:

- documentation for various open-source and proprietary third-party software (e.g., programming languages, queueing software, etc.)

- online materials from national ACI resources (e.g., XSEDE, OSG, etc.)

- open curriculum for live teaching via organizations like Software Carpentry and Data Carpentry

- institutionally-supported proprietary training services, like Lynda.com

- Wikipedia and other online information aggregators

- Question and Answer websites (e.g. Stack Exchange Network)

- Forums and other Community Driven Developments (e.g. mailing lists, Slack teams, etc.)

- books (where appropriate)

- faculty-developed, university-sponsored, or professional society courses

Beyond pointing to external learning resources via in-house materials and one-to-one assistance, Facilitators can also encourage researchers to participate in external learning opportunities, including the examples listed below:

- workshops by other local organizations

- semester-long courses at the local institution, perhaps relevant to specific research domains

- massively open online courses (MOOCs) on ACI-related topics

- workshops hosted by the technology industry (e.g., proprietary software companies, specialized hardware manufacturers, etc.), in addition to their online documentation

- materials, in-person courses, and webinars provided by national ACI resources (e.g., XSEDE workshops, annual Open Science Grid User School, etc.)

Based upon assistance and engagement interactions, Facilitators and ACI resource providers can list suggested external learning opportunities on their website and/or share such information to user email lists, as deemed appropriate.

Most importantly, external resources can and should be leveraged as examples by which Facilitators and other staff can construct clear and effective learning materials. To the extent that partners at similar ACI resource providers and/or institutions have already produced them, the Facilitator can also pursue options for re-using and/or adapting portions of these materials (with permission via communication or licensing), rather than composing materials from scratch. In fact, there are a number of efforts to produce shareable curriculum and/or arrange workshops specifically geared towards researchers who leverage ACI technology, such as the Software Carpentry and Data Carpentry organizations. In many of these cases, Facilitators may become certified trainers for such organizations or may otherwise arrange local workshops to teach the curriculum.

Organize and Promote Learning Materials for Ease of Use

To make the full set of learning materials easy to use, various topics and lessons should be arranged within an overall conceptual navigation structure, most typically in an online format (e.g.,. wiki, knowledge base, or linked set of simple web pages). This structure itself should inform or align with common pathways for incremental learning, though it can also be helpful to clearly delineate such pathways within introductory guides or to point to recommended next topics at the end of a lesson. For materials that are truly meant to be used in a linear fashion, learners will especially benefit from links to the “next” and “previous” topics. It should also be clear to learners how and when to access in-person versus self-help materials for various topics of interest.

When external materials are pointed to, content creators should make obvious to the researcher that these materials are external. Additionally, it is helpful to provide context for how the external materials fit into the specific context of relevant ACI systems and capabilities. As an example, a link to an external guide for the Unix Shell might come with context that the unix shell is available on the head nodes of the relevant compute center cluster. Similarly, in-house materials that are truly specific to particular ACI systems (per operating system, relevant use cases, job scheduling software, etc.) should be indicated as such within the overall organization of learning materials.

Obtain and Integrate Feedback

In order to assess the clarity and effectiveness of any learning materials or in-person sessions, it is important to obtain feedback from learners. As discussed more fully in Assessment and Metrics, such information can and should be obtained in different manners depending on the format of the learning opportunity. For in-person training, it is important to incorporate real-time feedback between learning modules (i.e., “lessons” or “topics”) via anonymous survey forms or free-form comments, which can inform pace and needs for clarifying previous concepts. Furthermore, pre-learning and post-learning surveys incorporated into in-person training efforts can indicate the extent of learning and the perceived importance of topics to inform future sessions. Surveys are also helpful for determining details about learners that inform the overall impact of education and training efforts for various demographics. For self-help materials, Facilitators and other ACI staff should encourage feedback from researchers regarding these materials whenever possible, and should also incorporate insights from assistance activities into content improvements and additions. Beyond informal feedback, regular surveys of the user community might include specific impressions of specific learning materials and the overall education and training approach of the ACI organization.

Infrastructure Needed for Material Development

When developing learning materials, there are a number of resources that allow for new materials and updates to be incorporated into existing materials. While the exact set of resources will differ based upon the format of the material, available tools, and preferences, we describe a few general considerations for development learning materials.

User-accessible publishing location

Firstly, materials should be developed with the specific intent of making these available to researchers in an easy to access location, most typically on the web. Even for in-person training materials, it is useful to publish these in a location that can be accessed by researchers before and after the learning session. When using an online repository (e.g., wiki, knowledge base, GitHub, etc.) that is separate from the primary webspace for a specific ACI resource, clear links to the repository should be used. Furthermore, the number of repositories for learning materials should be as minimal as possible, allowing for ease of navigation.

Composition environment

For ease of creating materials, the composition environment should be easy to use and include support for consistent formatting and publishing. For online materials, this may mean the use of templates or auto-formatting tools, which are typically built in to wikis or knowledge base environments. Furthermore, the environment should allow for easy editing of existing materials with automated updating to the publishing location. However, we acknowledge that the format of some materials, such as videos, dictate a development environment that is less amenable to additions and improvements.

Version and contribution history

Finally, content development will often benefit from the use of version control, to track past updates to materials and their contributors. The use of version history tools not only makes tracking contributions to materials easier across multiple contributors, but also keeps a record of the past states of any learning materials. For learners, “last updated” dates provide an indication of whether a self-learning guide is likely up-to-date, and contributor names will allow users to connect materials with Facilitators or other staff. However, as compared to the previous two development requirements, more compromises might need to be made for version and contribution history, depending upon the exact format of materials and external factors, including preferences among staff.

Jump to: top

Content Development Strategies

In this section, we summarize key strategies for designing and composing learning materials for the use of ACI resources, drawing heavily on tips from the literature on technical writing, documentation, and curriculum development. Because many of these ideas are repeated across the literature, we do not always cite them, though we provide a long list of these resources at the end of this chapter. Later, we discuss tips specific to the exact format of various learning materials, while the strategies below should extend well to nearly all format types.

Establish Goals of the Learning Material

Consistent across all of the literature is the idea that content in learning and documentation materials should be developed with clear learning goals.3 1 In order to develop the right materials for the information to be communicated, content developers should consider the following details in light of learning goals and leading practices in curriculum development and technical documentation:

- Which major style of informative material will be best?: concept guide (akin to our “education” definition), tutorial (“training”), or reference (akin to software manuals and indexes)? See 4 and other resources for more on these three styles.

- Furthermore, what amount of information should be presented within a unit of learning material, taking care to avoid concept overload?5 For example, some established tips for in-person and self-help tutorials indicate a general goal of 30 minutes for a single uninterrupted unit of learning material, especially for beginner tasks. 6 7

- Content should be evaluated against the goals for content and learning outcomes, both in the editing process and when designing assessments of learning.1

In addition to informing content development, the goals of any unit of learning material should be stated to learners in writing at the beginning of the unit, so that learners can determine the relevance for their learning needs. Especially for in-person learning opportunities, this information will help researchers to determine which sessions are worth their time and effort. Furthermore, it is important to tie guided training of specific tasks into the higher-level goals and best practices of any in-person session (covered more below in “Format-Specific Considerations”).

Clearly Communicate Prerequisites and Limitations

Content that builds upon prior information should clearly identify the knowledge and experience learners should already possess for maximum impact, beyond general considerations for determining the relevant audience. Similarly, any pre-requisites for existing access to any ACI systems or tools (including a user’s own laptop) should be indicated near the top of on-demand materials or be communicated in advance of in-person learning opportunities. Limitations and specific contexts for the tools and practices in the content should be clearly described, to inform a researcher’s decision to pursue solutions described in other content, as appropriate.

Organize Content within Conceptual Units

Within a single document or learning opportunity, different concepts, tasks, and examples should be clearly identified within learning materials. For example, a full set of information for a multi-hour training event should be divided into manageable subtopics or tasks, perhaps even as separate documents to follow during the training; variations of task examples within the same, short online guide should be labeled with distinct headings and be accompanied with task-specific descriptions. The organizational structure of these units should be provided in an outline-type list at the beginning of the learning material or presentation. In written formats, the structure of content should also be visually represented as distinct units, for example, by using unique formatting for headings, paragraph indentations, lists, and boxed text.

Clarity and Brevity

Beyond the use of proper grammar, punctuation, and active voice, there are well-established tips for achieving clarity in paragraph and sentence structure within written materials on technical topics, and with implications for verbal delivery (many are well-summarized and exemplified in 8) These tips are represented in the below list:

- Avoid jargon, seeking instead to find general terminology that will already be familiar to the audience.

- When introducing new, necessary terms, define them clearly and consider drawing visual attention with formatting.

- Use words efficiently, paring language down to essential messages and avoiding redundancy. Write in short paragraphs.

- Place key information and actions in the first clause of a sentence and in the first sentence of paragraphs, especially for tutorials, where action by the learner is frequently requested.

- Balance the focus on specific details with necessary context for interpretation and generalization.

- Select simpler terms over more complex synonyms (e.g "use" over “utilization” and “individual” over “individualized”).

- Identify potential ambiguity in wording, and use specific nouns over pronouns.

- Use strong verbs to achieve active voice (i.e. "arranged" over “made arrangements for”).

- Find a natural sound for active voice by reading passages out loud.

Clarity and brevity are also achieved via clear planning of overall content structure and concept ordering, in addition to the above tips for wording and in-text structure. Some forms of documentation for systems and tools may require exhaustive descriptions of features in order to serve as a reference. However, topic overviews and task-oriented guides, including those used for verbal formats, may be conceptually overloaded if too many edge cases or supplementary notes are included throughout. Rather, some of these might be better presented in special sections toward the end of a learning unit, perhaps under an “extra information” or “advanced” header.

Use Visual Aids

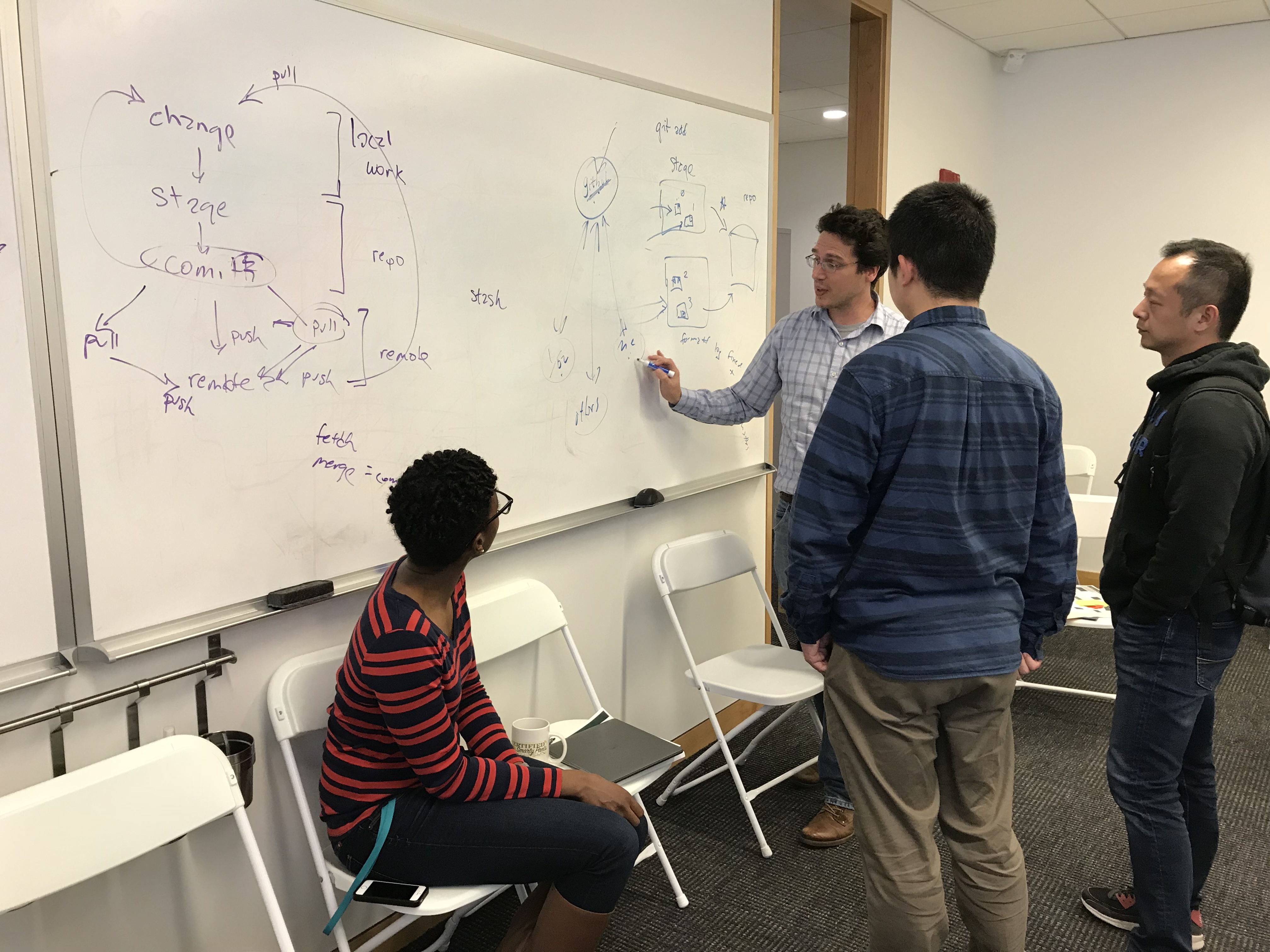

Visual aids help communicate systems, concepts and processes effectively

Visual aids help communicate systems, concepts and processes effectively

Visual aids should be incorporated to represent ACI systems, interrelated concepts, and decision processes, where applicable.9 Overall context in written and verbally-delivered materials is complemented by concept maps and flowcharts. Furthermore, visual representations can often replace long blocks of descriptive text and provide meaningful context for text. Diagrams of components within ACI systems can accompany descriptions of how these components interact in ways that are relevant for various use cases. Visual aids should be displayed during or near verbal descriptions, for maximum impact.

Assess and Revise, Continually

Content developers should repeatedly improve learning materials during the editing process, following informative feedback, and periodically revisit materials with assistance experiences in mind. For example, materials delivered in-person might be tweaked before each learning event, based upon lessons learned from a previous delivery. Regardless of the format, and because development of verbally-delivered materials also requires significant written composition, developers of learning materials should commit to writing as a process. This includes the cyclic progression from planning to writing and to revising, not just for individual modules and documents, but also for the holistic set of learning materials which may be maintained by more than one individual. In addition to planning out the content of new learning modules or lessons, developers should also plan time for the composition process, including time for review and testing by others.

Jump to: top

Format-Specific Considerations

- Written Materials

- Concept Overviews

- Tutorials

- Reference-style Documentation

- FAQs

- Verbal Formats

- Informational Talks

- One-to-Many Training

- One-on-One Training

- Videos

Written Materials

Building upon the general strategies for designing and composing learning materials, we discuss considerations specific to the three established goal-based types of technical writing: conceptual/topic overview, task-oriented tutorials, and references.9 We also include FAQ documents, as they frequently align with the learning needs of ACI users. As written materials are almost exclusively consumed via online interfaces, and readers of online information often skim rather than read exhaustively, the material should be composed and tested for clarity and completeness while avoiding unnecessary detail. The use of content modules and visual structure within a single, written document can be used to provide cues for learners to identify and locate the specific information they need.

Concept Overviews

Concept overviews or topical guides align most closely with our earlier definition of education materials. High-level descriptions are essential for introducing ACI resources, processes for obtaining access, and use cases, and provide learners with an essential foundation for more specific learning. While concept overviews can also dive into greater detail, the task-oriented needs of researchers using ACI are often better suited to tutorials (below). In light of previous composition practices, concept overviews are best written with a conversational tone.

Tutorials

As the most effective format for achieving guided instruction2, tutorials describing how to execute specific tasks will likely make up the bulk of learning materials composed by Facilitators and other ACI staff. Step-by-step use cases demonstrated in tutorials can be hypothetical, serving as examples upon which a researcher could construct a solution for their specific use case, or can be fully workable exercises to be executed exactly by the researcher before applying the overall process to their own case. For the latter approach, all materials (files or file contents), stepwise commands, and expected outcomes should be clearly described and presented, making up for the lack of live coding by an in-person instructor.

Reference-style Documentation

Reference materials documenting ACI features for various systems and software tools serve as an essential partner to high-level conceptual overviews and tutorials, including established examples for software ‘man’ pages and glossaries. While in-house references will likely only serve as extensive resources for in-house tools, other non-reference learning materials should point to existing external references for users desiring more in-depth and detailed information about specific features. For example, non-reference materials produced by ACI staff should include links to reference materials for established third-party software, though additional reference materials created in-house might provide a shorter reference for the most important features for such software (for example, the most common user commands for specific job scheduling software).

FAQs

A final and common form of written documentation for ACI resources is the Frequently Asked Questions or FAQ document, with practices drawing on a combination of those for other written formats. Because the FAQ is such a specific and pervasive format of documentation, numerous sources can be found on the web with common practices for generating effective FAQs, and therefore will not be cited here. Generally, FAQs should:

- include questions that are frequently asked

- be organized into groupings of similar concepts, in order to evoke high-level conceptual frameworks

- include the most essential and simple questions first, before listing less common and more complex questions

- directly answer the question, or at least point to additional information

- be updated frequently

- solicit new questions and communicate clear pathways for seeking answers and assistance

Overall, FAQs should be treated with the same development and editing processes as for other forms of written learning materials, even though they are often perceived to be a simpler form of documentation.

Verbal Formats

While written materials are more likely to include effort from other ACI staff, the verbal delivery of materials by Facilitators is important to the Facilitator-researcher relationship. Because many of the Facilitator activities documented here (Outreach, Engagement, Assistance, etc.) depend on some form of informative communication, verbal delivery by the same individuals will strengthen relationships with researchers and is likely to encourage more questions during an in-person learning session. Even with superbly-developed materials to guide verbal delivery, good teaching often comes down to the aspects that are unscripted, including two-way interactions between instructors and learners. Well established practices for live teaching and verbal communication exist in a variety of summative resources (including 10 11 7). Furthermore, Facilitators can also leverage workshops and other training materials for developing good teaching skills.

Ultimately, prevailing wisdom indicates that the development of good teaching skills relies heavily on watching others teach and on repeated teaching experiences, with significant benefit from the implementation a few specific practices. For teaching skills relevant to ACI, teachers should implement proven practices for well-paced live examples so that learners can follow along.2 12 7 In class exercises and discussion should include opportunities for peer-learning and pair programming, perhaps by encouraging more advanced learners to assist others who may be struggling.13 12

Effective teachers leverage practices for gauging and motivating learning, in real time, including frequent opportunities for questions and feedback, in addition to reading visual cues for which students are struggling. Teaching that empathizes with learner frustrations and motivating factors is essential, even for Facilitators who naturally identify with the typical struggles of researchers in learning ACI topics and is based upon their own experiences. To avoid demotivation of learners, instructors who have significant expertise over learners should leave out personal perceptions of ease and complexity, in order to avoid clashing with learner perceptions, and should avoid condescending language like the word “just”.107

While instructor’s should establish trust in their expertise and recommendations, learners will ask more questions and seek help when instructors are frank about their own knowledge limitations.7 Furthermore, instructors should revisit learner motivations and expectations for a particular learning opportunity by frequently tying specific concepts and tasks to desired goals, outcomes, and leading practices for using ACI in real-world use cases.10

Beyond the above practices for live instruction, we specifically discuss considerations for various types of verbally-delivered learning sessions, including information talks, training in one-to-many and one-to-one formats, and one-way verbal teaching through recorded videos.

Informational Talks

Typically, informational talks will follow the style of education and concept overviews over tutorials for training, although a combination of styles may be employed in the same learning event to achieve holistic learning outcomes and provide variety. For example, an information talk introducing a computing cluster and forms of compute parallelization may precede intro tutorials for basic use of a cluster. Otherwise, lone informational talks are very similar to outreach, drawing on the same leading practices for content development. However, the inclusion of hypothetical examples for executing ACI tasks, within an informational talk, can serve as a form of guided instruction and is especially effective if the presentation materials or a recording are made available.

One-to-Many Training

As compared to informational talks, training in a classroom or similar in-person format often takes the form of tutorials. These tutorials may be introduced with short or long periods of informational talks in some cases. (Software Carpentry workshops and curriculum, for example, focus mainly on hands-on guided practice with bits of explanation prose along the way.) Importantly, one-to-many training materials can often serve double-duty for in-person and self-help learning, if made publicly available beyond their use at in-person learning events.

One-on-One Training

Training in a one-to-one format with single or few researchers will typically resemble Assistance meetings and office hours, where practices of pair-programming and guided instruction (having researchers learn by doing) are most effective. See more discussion in Assisting Researchers in the Use of ACI Resources.

Videos

Because videos lack the typical two-way communication opportunities that allow teachers to adapt in light of learner feedback and misunderstandings, content development for videos (or even audio) faces the same challenges for completeness and anticipation of difficulty as for written guides. Therefore, the selection of materials to be presented in videos should be well-informed by common questions and difficulties observed from in-person assistance and teaching experiences, and should depend on content completeness that has been well-tested in other formats. While frequent updating and editing of video-based learning materials is often more difficult without completely re-recording the video, some technologies and video formats can make this process a bit easier.

Jump to: top

Promoting Learning between Researchers

In addition to providing learning materials for researchers and otherwise pointing researchers to materials that exist elsewhere, it is also important to remember that researchers with similar ACI challenges or in similar research areas might also learn a lot from each other. To the extent that Facilitators record engagements and ACI plans and are otherwise aware of researcher needs and solutions via assistance practices, Facilitators can also connect researchers to each other. Contexts for such connections might include instances where multiple researchers:

- work in the same research group, and one is newer to the ACI resource

- are pursuing similar research methods

- rely on the same software

- require the same specific features of an ACI resource (or its configuration)

Learning from peers can be thought of as simply another form of external learning resource, not produced or maintained by the Facilitator or other ACI staff. Approaches for connecting researchers in order to promote knowledge exchange,often referred to in the context of CI as technology exchange, are more fully discussed in the chapter on Facilitating Connections, including examples of facilitating researcher communities around specific ACI topics and research methods. Some ACI organizations and Facilitators even host repositories for researcher-produced (but Facilitator-vetted) documentation for very specific tasks and workflows on ACI systems to serve as examples other researchers. (For more information on the significant benefits of peer instruction and pair programming, see 14, and 13.)

Jump to: top

References

-

Baume, David. Writing and Using Good Learning Outcomes. Leeds: Leeds Metropolitan U, 2009. Print. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Kirschner, Paul A., John Sweller, and Richard E. Clark. “Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work: An Analysis of the Failure of Constructivist, Discovery, Problem-Based, Experiential, and Inquiry-Based Teaching.” Educational Psychologist 41.2 (2006): 75-86. Print. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Guzdial, Mark. Learner-centered Design of Computing Education. San Rafael: Morgan & Claypool, 2015. Print. ↩

-

Bellamy, Laura, Michelle Carey, and Jenifer Schlotfeldt. DITA Best Practices: A Roadmap for Writing, Editing, and Architecting in DITA. Upper Saddle River, NJ: IBM, 2012. Print. ↩

-

Mayer, Richard E., and Roxana Moreno. “Nine Ways to Reduce Cognitive Load in Multimedia Learning.” Educational Psychologist 38.1 (2003): 43-52. Print. ↩

-

Kaplan-Moss, Jacob. “What to Write.” https://jacobian.org/writing/what-to-write/ Web. 2009. ↩

-

Wilson, Greg (ed). “Software Carpentry: Instructor Training.” http://swcarpentry.github.io/instructor-training/. Web. 21 March 2016. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

Kelly, Nicole. “Sentence Structure of Technical Writing.” http://web.mit.edu/me-ugoffice/communication/technical-writing.pdf. Web. 21 March 2016. ↩

-

Hargis, Gretchen. Developing Quality Technical Information: A Handbook for Writers and Editors. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall Professional Technical Reference, 2004. Print. ↩ ↩2

-

Ambrose, Susan A. How Learning Works: Seven Research-based Principles for Smart Teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2010. Print. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Lockee, Barbara B., P. De Bruyckere, P. A. Kirschner, and C. D. Hulshof. “Urban Myths about Learning and Education.” TechTrends TECHTRENDS TECH TRENDS 59.6 (2015): 53-56. Print. ↩

-

Wilson, Greg. “Software Carpentry: Lessons Learned.” F1000Research F1000Res (2014). Print. ↩ ↩2

-

Porter, Leo, Mark Guzdial, Charlie Mcdowell, and Beth Simon. “Success in Introductory Programming.” Communications of the ACM Commun. ACM 56.8 (2013): 34. Print. ↩ ↩2

-

Crouch, Catherine H., and Eric Mazur. “Peer Instruction: Ten Years of Experience and Results.” Am. J. Phys. American Journal of Physics 69.9 (2001): 970. Print. ↩