Assisting Researchers in the Use of ACI Resources

Assisting Researchers in the Use of ACI Resources

Establishing proactive and reactive support routes for researchers who use ACI resources, including standards of response. Promoting learning and user empowerment in providing support for user-reported or observed issues. Leveraging external technical expertise.

- Introduction

- Establishing Communication Routes for Providing Assistance

2.1 Common Assistance Routes

2.2 Promoting Awareness of Assistance Routes - Effective Communication in Assistance Interactions

3.1 Professionalism and Empathy in Assistance Communication

3.2 Achieving Clarity in Complex Assistance Discussions

3.3 Assistance Strategies that Advance Researcher Capabilities - Addressing User-Reported Issues

4.1 Clarify the User’s Problem

4.2 Identify Issue(s) and Appropriate Solution(s)

4.3 Communicate Next Steps to the User - Assistance for Non-Issue Support Requests

5.1 Understand the User’s Most Immediate Question(s)

5.2 Anticipate the Real and Next Questions

5.3 Empower the User to Find Her/His Own Answers - Proactive Support

- Reflection on Assistance Experiences

- References

Introduction

Assisting researchers as they actively use ACI is a key component of facilitation, especially if the Facilitator is directly associated with one or more specific ACI services or when researchers require outside resources. Whether researchers are already leveraging an ACI resource or have just gained access, they should be be able to easily obtain ongoing assistance from Facilitators and other ACI support staff with respect to:

- questions about ACI capabilities and use

- requests for help with issues

- needs for learning materials

- requests for engagement consultations or other guidance for new ideas

- obtaining assistance for external ACI resources

Therefore, an essential component of providing assistance is to establish consistent and accessible routes by which users can obtain assistance and to establish a set of effective communication practices. As described later in this chapter, assistance communication should strive to be as clear as possible, regardless of the assistance route, and present solutions that advance a researcher’s own future capabilities in using ACI resources. We also discuss the importance of translating assistance experiences into improvements to learning materials (see also Education and Training of Researchers) and into optimization of ACI system capabilities to better meet researcher needs (covered in Interfacing with ACI Resource Providers).

For the purpose of distinguishing the information in this chapter from that in Engaging Researchers, we define “assistance” as the one-to-one or one-to-few support of researchers already accessing an ACI resource, where the support pertains directly to their specific practices in using that resource. Assistance may follow from an engagement, especially if the engagement results in the researcher using ACI for the first time. It is also important to note that some interactions with researchers may be a combination of engagement and assistance, or may transition from one to another. For example, assistance discussions lead to a redefinition of the ACI Plan and/or the need for another ACI resources is recognized. As described above, assistance routes are also an important avenue by which a researcher may request a new engagement meeting.

Jump to: top

Establishing Communication Routes for Providing Assistance

To effectively support researchers in their use of ACI resources, a set of routes by which researchers can obtain assistance should be well-advertised. It is crucial to utilize multiple established communication routes for assistance when the Facilitator most directly supports a specific ACI resource (a campus computing center, for example). Facilitators should also be aware of and clearly identify external assistance resources, especially those of external ACI resources (e.g., other institutional ACI resources, national computing centers, commercial cloud services, etc.). Below, we discuss the implementation and applicability of several communication routes for providing assistance, and later discuss effective communication strategies.

Common Assistance Routes

While each of the below communication routes for providing assistance is powerful on its own, it is valuable to have multiple routes from which to choose to cater to various situations and researcher preferences. At the same time, it is a good strategy to avoid having too many routes, so as not to overwhelm researchers with the number of choices and so that the options are clear to researchers.

Email and email-based ticket systems

In comparison to other assistance routes, email is often best for addressing issues that can be easily understood and whose solutions can be readily communicated without the need for significant back-and-forth conversation. Email contact is also the most common gateway to other assistance routes, especially when contact is initiated by the Facilitator. Finally, email follow-ups can and should be used after providing assistance to a researcher via one of the other assistance routes, in order to recap the conversation and to document specific details that the researcher may not have recorded or remembered.

Many ACI organizations leverage an email-based ticket or other issue tracking system for managing and responding to user support requests. This approach typically provides a convenient, single point of access for email-based support requests from users, allow a consolidated view of past issues and requests, and come with built-in features for ease of collecting metrics. Alternatives include the use of a single, dedicated email address monitored by one or more Facilitators and possibly other ACI staff, as long as the ownership of each new request can be made clear among these staff. Typically, individual staff email addresses are much less effective and add unnecessary confusion for users, especially if there are multiple individuals providing assistance or when staffing changes occur. Furthermore, the use of individual email addresses often leads to confusion between multiple Facilitators when assisting the same user(s), over time, and can impede the collection of metrics.

Scheduled appointments

There are times when email (or any other assistance route) may be insufficient, such that a scheduled, and preferably in-person, meeting is necessary. Examples include, but are not limited to, issue troubleshooting that would require many back-and-forth emails, instances where a researcher isn’t sure how to start using an ACI resource or how to explain their problem, and even a researcher’s preference for in-person communication instead of email. Effective in-person meetings draw on many of the same practices as for engagements, including:

- selecting a meeting location that is accessible to the researcher

- understanding the full problem or question from a researcher before beginning to pursue solutions

- clearly communicating and explaining next steps

- making sure to follow-up with the researcher, as appropriate

Additionally, and distinct from practices typical to an engagement, it is most effective to have a researcher execute a solution for themselves, rather than only demonstrating the solution while the researcher watches. Assistance meetings (and office hours, below) have an added benefit over email communication in that they allow Facilitators a unique look into the regular practices and hiccups of ACI users when working side-by-side (see 1, for more on pair programming benefits). Furthermore, in-person contact provides many more communication context clues, with the visual recognition of facial expressions and body language. However, scheduled video and telephone calls may be necessary if an in person meeting is problematic (see further below).

As a reminder, many scheduled meetings may involve assistance for specific tasks and discussion of ACI planning, or may transition from one to the other.

Office hours

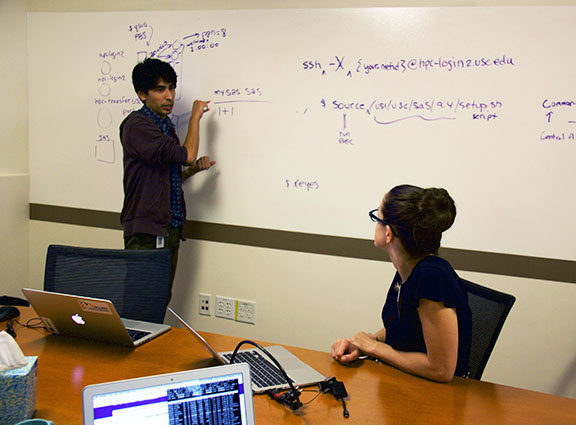

An ACI-REF helps a researcher during Office Hours.

An ACI-REF helps a researcher during Office Hours.

Regularly scheduled office hours are often an effective complement to other assistance routes, especially if the assistance conversation may not warrant the scheduling of a special meeting but would still benefit from in-person communication that might otherwise take multiple emails. Furthermore, office hours cater to user preferences for face-to-face communication, and allow researchers to drop in without the waiting time that may be necessary for a scheduled, dedicated meeting. Office hours are most effective when provided at consistent and convenient times, and in accessible locations. This may mean that office hours are held at different times, on different days of the week, or in different locations on different days of the week, in order to maximize the likelihood that at least one of the office hours slots and locations will work for a given researcher.

Depending on the popularity of office hours, it may be necessary to have multiple Facilitators (or similar individuals) at a given session, or to have other ACI staff prepared to assist should office hours become too busy for a sole person. As office hours are otherwise very similar to scheduled meetings in that they are usually executed in a face-to-face manner, the leading practices of assisting an individual researcher are the same for both, while acknowledging the potential need for juggling more than one researcher’s concerns at the same time during office hours.

On-demand options (chat, phone, etc.)

With the popularity of new technologies and social media, there are a number of other routes which have been effectively leveraged for providing assistance to researchers needing support. For example, chat rooms and messaging services can be leveraged with a hybrid set of best practices drawing from email and in-person assistance. Phone calls may be effective when email is perceived to be insufficient and when a convenient location for in-person assistance is not possible. These and other less common routes not discussed here can be implemented, according to the Facilitator’s best judgement regarding applicability and leading practices, drawing on similarities with the previously-described routes.

As technology preferences and other factors shift researcher and Facilitators practices toward additional assistance routes, the set of most common and recommended routes described here should be amended, but with the same goal of providing the most effective support to ACI users. Across the various communication pathways for providing assistance, and regardless of the purpose of the communication – follow-up with user, resolving user issues, proactive support – there are a number of best practices for providing assistance that are covered further below in “Effective Communication in Assisting Researchers”.

Promoting Awareness of Assistance Routes

Just as it is important to promote awareness of ACI resources and facilitation services to researchers (as described in Outreach), it is also essential to adequately document and promote the ways that researchers can obtain assistance from Facilitators (and/or other ACI staff). Typically, this information can be listed alongside in-house learning materials and troubleshooting documentation on a website (see Education and Training of Researchers). For example, it may be effective to provide a dedicated web page discussing the routes via which assistance can be pursued, and to remind researchers of support mechanisms within other online documentation pages. Furthermore, the options for assistance should also be discussed during engagements and in follow-up correspondence, perhaps as part of the ACI Plan communicated to the researcher. Additionally, discussion of available assistance routes may be included in outreach materials, in part, to demonstrate the extent of support for researchers who might need to leverage ACI in the future.

Jump to: top

Effective Communication in Assistance Interactions

Regardless of the assistance route, and in order to establish trust in the Facilitator, assistance communication should be clear to the researcher and be performed in a professional manner. Furthermore, as the primary goal of facilitation is to truly accelerate research, assistance strategies should clearly communicate approaches, enhance each researcher’s capabilities, and empower the researcher to achieve more in the use of ACI resources into the future. We discuss below these overall considerations, which apply to multiple assistance contexts covered below, including “Addressing User-reporting Issues”, “Assistance for Non-issue Support Requests”, and “Proactive Support”.

As Facilitators will often rely on assistance participation or input from other ACI staff, it is crucial that they strive to ensure that their fellow ACI staff maintain these same standards of practice when communicating with researchers. Often, Facilitators can be a crucial, clarifying, and resounding voice by remaining involved when issue resolution is taken on by another staff member.

Professionalism and Empathy in Assistance Communication

Regardless of the assistance route, it is important to distinguish assistance and other communication with researchers from internal-issue communication between ACI staff. Doing so fosters better relationships and a two-way, “beyond the help desk,” communication culture that is more akin to collaboration between colleagues. Such a distinction is central to establishing a supportive relationship and is essential to the role of Facilitators. Beyond professionalism, a colleague-like relationship with researchers is also best achieved by treating researchers and their potential misunderstandings with respect and empathy.

Because each researcher has a unique background of experience with and understanding of ACI concepts, assistance communication should recognize this uniqueness and strive to instill confidence of the researcher in their own abilities and in the Facilitator. Empathy for the difficulty a researcher may face in learning ACI skills is one of the arguments for Facilitators themselves to possess experience with implementing ACI resources for research projects (see more about peer instruction in 2 and 1). Rather than discouraging the researcher from asking questions that they might believe to be naive, assistance practices should encourage researchers to seek more answers in a combination approach of learning for themselves and being comfortable in seeking assistance in the appropriate circumstances.

The importance of professionalism and empathy is often overlooked in email communication for user support. It is therefore important to follow typical practices for professional email communication, including the use of greetings and introducing your name and role in the email body and/or closing signature. Good examples of this are shown below, under the topics of “Addressing User-Reported Issues” and “Assistance for Non-Issue Support Requests”. Even for messages sent via email-based issue “ticket” systems, where there may be a tendency to leave out greetings and closing statements, it is important to treat communication with users with more formalism than the styles culturalized in email communication between ACI staff. For this reason, the Facilitator and ACI service provider may find it useful to separate internal communication from that used to communicate with researchers, perhaps by using separate ticket queues. Furthermore, any communication that would demean a researcher for misunderstanding or lack of knowledge, or that might discourage researchers from pursuing assistance in the future, should be strictly avoided.

Achieving Clarity in Complex Assistance Discussions

A primary impetus for the assistance role of Facilitators is that researchers often benefit significantly by having a translator of complex concepts and terminology when learning to effectively utilize ACI resources. To this end, Facilitators must strive to find language that is already familiar to researchers, especially for assistance communication. As discussed more thoroughly in Educating and Training Researchers, education research indicates that non-experts are more effective in teaching concepts that are novel to learners, as teachers with greater expertise already possess a more sophisticated understanding and set of terminology (see 3 and 4 for more discussion on this topic).

Other specific guidelines for clear wording in any communication context are:

- Describe concepts succinctly and in the simplest terms possible. It’s often useful to re-read and consolidate or shorten written information before sending.

- Use specific nouns to identify relevant items and concepts (e.g. “the submit file”, “your software”, “the file transfer rate”), and avoid less-specific pronouns as much as possible (e.g. “it”, “they”, “them”).

- Avoid jargon specific to an expert understanding and strive to find terminology that is familiar to the researcher. For example, use “program” or “software” if the word “executable” is less familiar.

- Avoid overwhelming the researcher with too much new information at once. Please see Educating and Training Researchers in the Use of ACI, 3, 5, and 6 for more discussion on concept/cognitive overload.

- When introducing new terminology and ideas, as necessary define terms and provide distinction from other concepts. For example, “the submit file, which will be separate from the BLAST alignment program you wish to run within each job ...”.

- Minimize the use of acronyms by limiting these to terms that are: (1) already familiar to the researcher, and/or (2) have been sufficiently defined and used previously in non-acronym forms.

Facilitators may benefit from a plethora of existing literature and professional development opportunities to develop excellent communication skills. In later sections, below, we elaborate more on assistance approaches that are more specific to assisting with issues, reaching beyond effective communication to include strategies for selecting solutions and recommendations.

Assistance Strategies that Advance Researcher Capabilities

As previously stated, a key role of a Facilitator is to enable researchers to achieve more for themselves than they might have thought possible or what might have been achievable with a reactive, issue-focused strategy of support common to help-desk environments. For the Facilitator, this often means pursuing assistance that teaches a research to “fish for her/himself”. Rather than directly solving issues for the researcher or only suggesting easy to implement, short-term solutions, Facilitators should strive to identify and recommend solutions that enable researchers to accomplish more and to imagine greater research possibilities, in the long-term. The communication of solutions should be presented, as much as possible, as a form of guided instruction.7

To achieve the proper balance and to assist researchers in deciding for themselves which solutions to pursue in various cases, there are a number of specific strategies that effective Facilitators should implement. Firstly, it is important to consider various options relative to both the researcher’s immediate needs and long-term goals. Additionally, the Facilitator should explain reasons for recommending a specific solution over others, especially when an easier but less impactful solution may already be apparent. Facilitators should also explain their level of confidence in the researcher’s ability to implement various approaches or solutions, potentially based upon demonstrated success from other research examples, and should provide clear suggestions that the researcher can follow to achieve and assess stepwise success.

Beyond explaining solutions, Facilitators can also improve the researcher’s capabilities by teaching them how to troubleshoot and seek answers for themselves in the future. Beyond explaining the Facilitator’s thought process in determining appropriate solutions, a Facilitator can establish examples of useful information sources, including in-house learning materials and information sources (online or elsewhere) deemed to be effective and trustworthy by the Facilitator and other staff. Additionally, Facilitators can check in proactively when issues or optimization opportunities are detected by various ACI staff from usage metrics (as described further in “Proactive Support”).

Jump to: top

Addressing User-Reported Issues

Although the nature of issues reported by users of ACI resources will vary significantly between resource type, the basic practical steps for troubleshooting and problem-solving are fairly general: seek evidence, diagnose, identify and test solutions or workarounds, and implement and/or communicate solutions. Regardless of whether an issue is simple, such as an easy-to-fix user error, or one which requires significant effort from ACI staff, there are several basic steps for communicating solutions and for capitalizing on assistance requests for teaching opportunities.

Clarify the User’s Problem

Assistance-providers may first need to interpret the researcher’s reported problem by asking any clarifying questions and by stating the problem back to the researcher before proceeding further. This step will confirm the issue with the researcher and may train the researcher to provide pertinent details of what they observe early on in future help requests. If multiple problems were reported or the Facilitator perceives that there may be more than one issue at play, these should be stated and addressed, separately.

Identify Issue(s) and Appropriate Solution(s)

After the user’s problem has been clarified, typical problem solving steps can be followed to identify the source of the problem and to evaluate solutions. This process may require the involvement of other ACI staff or further input from the researcher. First, evidence of the issue should be identified with help from the researcher, perhaps by examining user files, user-provided error messages or file contents, and/or indicators in system log files and metrics. After determining the reason for the issue, it may be necessary to reproduce it, depending on the exact problem, context, and precedents, and to potentially involve other ACI staff. If a solution is not immediately obvious, and/or requires more work, it may be necessary to provide the researcher with an update, in order to communicate a potential resolution timeline.

Communicate Next Steps to the User

After selecting a solution for the issue, the Facilitator should communicate this solution to the researcher, making sure to clearly describe steps for implementing the solution. The source of the issue should be explained clearly in order to provide context for the effectiveness of a chosen solution. When more than one solution may be appropriate, the Facilitator should explain reasons for suggesting a specific solution. It may also be appropriate, and will certainly enhance the user’s own future capabilities, to prepare the researcher for potential, related issues that might arise in the future. Importantly, such discussion should still be limited to a scope that will not overwhelm the researcher with too much information, and suggesting a follow-up meeting may be beneficial to ensure the best, stepwise progression for solving a complex issue.

The following is an example of the above practices in an email communication with a researcher:

------------------------

Hello,

I tried to use ‘scp’ to copy data to my user directory on host1.org.univ.edu,

but I get a “Permission denied” error. Is something wrong with my account?

-John Scientist

------------------------

Hi John,

Thank you for writing to us with this question. In order to understand why

your scp command isn’t working, can you send me the exact command you’re

using and the terminal output when you run the command? From what I can

tell, there doesn’t seem to be anything wrong with your account,

but we’ll figure out what’s not working.

Thank you,

Michelle Facilitator

Research Computing Facilitator, CHTC

-------------------------

Hi Michelle,

Here are the lines from my terminal:

JohnDesktop:~ JohnSl$ scp myfile host1.org.univ.edu:/home/jscientist

jscientist@host1.org.univ.edu's password:

scp: /home/jscientist/myfile: Permission denied

-John

------------------------

Hi John,

Ah. I think I see what’s wrong. When you use ‘scp’ from your desktop, the

‘scp’ program assumes that you’ll be connecting as your Desktop username

(“JohnS”) unless you specify that your username on the server is different.

Our own guide for file transfer has some examples explaining this behavior

and other scp features (org.univ.edu/guides/filetransfer.html), and there is

even more information online if you Google something like “scp guides”.

Here’s a command that should work for you:

scp myfile jscientist@host1.org.univ.edu:/home/jscientist

Thank you,

Michelle Facilitator

Research Computing Facilitator, CHTC

------------------------

Record communication for re-use

Some issues are reported more frequently than others. Solutions for these common issues must be recorded in an easily accessible location, for instance, in the “Frequently Asked Questions” (FAQ) section of the documentation for the ACI resource. It should be made clear to users that this location must be consulted before request for assistance, but these issues may be reported in assistance routes nevertheless. Other issues may still require examination on a case-by-case basis but may need only minor “tweaks” for each user. It is important that the Facilitator identifies such recurring issues, and prepares a “template” communication that can be reused each time. Tools like Canned Responses may be very useful for this.

Jump to: top

Assistance for Non-Issue Support Requests

Often, users may contact Facilitators to discuss questions about ACI options, capabilities, and modes of use. Typically, these questions differ from assisting with issues in that the user hasn’t encountered a specific difficulty in using an ACI system. Instead, these questions are more general and more proactive. These questions can be addressed with targeted clarification and guidance or for which existing education and training materials will be sufficient.

Examples of non-issue requests can include:

- What is the best way to run software “X” on the compute system?

- How much data can I store?

- Does anything on campus support my ACI need for “X”?

- I’m about to start on a project and I wanted to ask about “X”.

When addressing such questions, a slightly different approach for information exchange may be appropriate, as demonstrated in the below steps, though the overall process is still very similar in some ways to issue resolution. Some non-issue questions may actually lead to a true engagement, where a more complex ACI plan can be discussed. However, the progression to deciding if an engagement is necessary would still follow the first few steps below and according to practices described in Engaging Researchers. As a clear demonstration, we provide two simple examples of email communication for non-issue requests, though the same ideas would apply within the context of other assistance route(s).

Understand the User’s Most-immediate Question(s)

After receiving a non-issue question from a researcher, it is important to fully understand the researcher’s intent and the scope of information they’re seeking within the context of what the Facilitator already knows about the researcher’s relevant ACI knowledge, as is demonstrated in the following exchange:

------------------------

Hello,

How do I run Matlab on multiple processors?

-Jane Biologist

------------------------

Hi Jane,

Thank you for writing to us with this question. I believe this will be

your first time running Matlab jobs at our center. Are you wondering how

to run many Matlab jobs at once, where each might use a different processor,

or how to run a single Matlab job that utilizes multiple processors?

I can even help point you in the best direction if you can explain a bit

about what your Matlab program is doing, in terms of your research, and how

it is using input data. Additionally, how might this work expand for you

in the future if you could get it running efficiently in our compute systems?

Thank you,

Michelle Facilitator

Research Computing Facilitator, CHTC

-------------------------

Hi Michelle,

I would like to run my Matlab script that simulates genetic variability at

least 1000 times, where each simulation uses the same genetic variation file

and a unique set of parameters from my parameter file. This many simulations

would take more than a week on my Mac, and I know that Matlab can be run on

clusters using multiple processors at once, so that all 1000 simulations run

faster. How many processors can I use for running this Matlab program on

cluster A? Eventually, I’ll want to do the same for several different genetic

starting points (variation files).

-Jane

--------------------------

Anticipate the Real and Next Questions

In some cases, the original question(s) may be limited by the researcher’s current knowledge of ACI such that the researcher is actually seeking an answer to a slightly different question or such that the researcher’s goals can be best addressed by a different solution than originally suggested. Additionally, the Facilitator may be able to anticipate and answer other questions in order to reduce the amount of back-and-forth communication. Inviting a transition to an in-person meeting – perhaps more similar to an engagement – may even be a more appropriate solution for assisting the researcher.

------------------------

Hi Jane,

Thank you for the additional information. Based upon what you’re

describing, I believe you can accomplish more by running many separate

Matlab jobs that each use a single processor, instead of being

limited by how many processors a single Matlab job can run on. Our

cluster B is ideal for this type of high-throughput computing (HTC) work,

and you will likely find that you could easily run more simulations with

more parameters than on our Cluster A; you’ll also be able to repeat that

many simulations for the different genetic starting points you describe.

As you might imagine next, this approach will mean that you will want to

slightly rework your Matlab program a bit to read in a single parameter file,

each time, in addition to reading in the genetic file. So you’ll also want

to pre-create separate parameter files that each only have the relevant

parameters for a single simulation. Let me know if you’d like pointers

in Matlab’s documentation on how to read in the files or ideas for breaking

up a parameter file.

Our own online guides for how to set up and submit many single-processor

Matlab jobs is here: www.compute-center.school.edu/htc-matlab-jobs

Let me know if you have any questions about the above information. We can

always meet to discuss more, if you like. ‘Sound good?

Michelle

--------------------------

Empower the User to Find Her/His Own Answers

As demonstrated in the Facilitator’s response above, it is important to link to external resources that contain solutions for achieving a researcher’s goals. This practice is not only important for providing next steps, but also demonstrates how one might find answers to such questions more quickly in the future, as was hinted in the prior example. Another example of these practices is provided below:

Hello,

I have been using the nano text editor on the cluster servers, but I hear

that other text editors have more options. Which text editor would you suggest?

-Zoe Chemist

------------------------

Hi Zoe,

My personal favorite for the command-line is the ‘vim’ text editor, which

is on just about any Linux server. You can certainly find a number of online

tutorials in various formats, by searching online for “vim text editor guide”.

You can also find many online comparisons of text editors beyond ‘vim’ by

searching for something like “which command line text editor is best?”. There

are heated debates, and most people who use the command line have strong

preferences, but the information you find will likely help you decide which

text editor you might prefer. I prefer ‘vim’ (sometimes referred to as ‘vi’)

because it is more powerful than ‘nano’, with a moderate number of standard

options. I’d be happy to discuss more, if you like.

Cheers,

Michelle Facilitator

-------------------------

While it should always be the goal of a Facilitator to enable researchers to do more for themselves, indicating how a researcher can find her/his own answers should not be intended to discourage the researcher from seeking assistance from Facilitators and other staff. Facilitators need to find a balance between empowering researchers to learn to find their own answers while still welcoming future assistance requests, as needed.

Jump to: top

Proactive Support

Proactive user support can be thought of as assistance initiated by the Facilitator rather than by a user of an ACI resource. It might be helpful to the researcher when a Facilitator occasionally checks in, not only when indications of difficulty become apparent (in user metrics, for example), but also to understand how a researcher’s use and satisfaction of ACI may have evolved. Often, but not always, proactive assistance may even evolve into conversations more akin to engagements.

This particular activity is perhaps the most important component distinguishing the facilitation approach from more common approaches of supporting users of CI, whereby researchers are provided with written documentation and are left to initiate contact with Facilitators. Proactive assistance allows Facilitators to build upon relationships with researchers and, more importantly, to identify issues that users may not think to ask about.

A few possible reasons to proactively contact a user are:

- Metrics indicate misuse of an ACI resource.

- Metrics indicate that a user’s work may be better optimized.

- A sudden increase in the user’s activity potentially indicates a new type of work with different resource needs to address.

- The Facilitator believes a follow up to previous assistance may be helpful, perhaps after reviewing tickets.

- The Facilitator may simply want to check in with a long-time user who hasn’t written in with any issues in some time.

If the reason for contacting the researcher is more akin to issue resolution or proposing enhancements to the researcher’s use of ACI, the Facilitator will likely follow assistance communication steps as described in previous topics of “Addressing User-reported Issues” and “Assistance for Non-issue Support Requests”. However, simple follow-ups regarding the researcher’s assessment of ACI resources and services, his/her evolving research goals, or simply to see how things are going will likely follow more of a casual interview. If the Facilitator has specific goals in contacting the researcher, preparing a set of specific questions will be helpful. More information on understanding researcher attitudes using interview-like interactions is available in Assessment and Metrics.

Jump to: top

Reflection on Assistance Experiences

Over time, Facilitators will most likely identify common needs, misunderstandings, issues, etc.. In such instances, Facilitators are ideally poised to understand and represent the evolving needs of the user community in order to inform future changes to support routes and ACI systems that may include:

- Changes in practices relevant to engagement and assistance

- Improvements or additions to outreach and education/training approaches and content

- Improvements to and selection of middleware and other mechanisms by which users interact with ACI (e.g., user interfaces, selection of compute scheduling middleware, etc.)

- Configuration adjustments to ACI systems/technology that enhance user outcomes (e.g., enhancements to ACI system availability, optimizations to compute scheduling efficiency, etc.)

- Enhancements to existing ACI resource capabilities and/or capacity

- Policies and cost models governing user access to ACI resources and capacity

- Addition of new ACI resources and capabilities

Importantly, Facilitators need built-in communication pathways and working relationships by which feedback regarding the above areas can be readily communicated to ACI resource providers and technology specialists, as described further in the chapter on Interfacing with ACI Resource Providers. To the extent that the above ACI changes might be informed by measures and systematic evaluation, additional considerations are covered in Assessment and Metrics.

Jump to: top

References

-

Porter, Leo, Mark Guzdial, Charlie Mcdowell, and Beth Simon. “Success in Introductory Programming.” Communications of the ACM Commun. ACM 56.8 (2013): 34. Print. ↩ ↩2

-

Crouch, Catherine H., and Eric Mazur. “Peer Instruction: Ten Years of Experience and Results.” Am. J. Phys. American Journal of Physics 69.9 (2001): 970. Print. ↩

-

Ambrose, Susan A. How Learning Works: Seven Research-based Principles for Smart Teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2010. Print. ↩ ↩2

-

Dreyfus, Stuart E. “The Five-Stage Model of Adult Skill Acquisition.” Bull Sci Technol Soc Bulletin of Science, Technology and Society 24.3 (2004): 177-81. Print. ↩

-

Mayer, Richard E., and Roxana Moreno. “Nine Ways to Reduce Cognitive Load in Multimedia Learning.” Educational Psychologist 38.1 (2003): 43-52. Print. ↩

-

Wilson, Greg (ed). “Software Carpentry: Instructor Training.” http://swcarpentry.github.io/instructor-training/. Web. 21 March 2016. ↩

-

Kirschner, Paul A., John Sweller, and Richard E. Clark. “Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work: An Analysis of the Failure of Constructivist, Discovery, Problem-Based, Experiential, and Inquiry-Based Teaching.” Educational Psychologist 41.2 (2006): 75-86. Print. ↩